|

Kangerdlugssuaq melting

You ever commute to work, and find your

office building missing when you get there? That's probably what it felt

like this Monday morning for University of Maine glaciologist Dr. Gordon

Hamilton.

He

was commuting to his place of work (a glacier of course) with Hughie,

flying the helicopter, and Melanie, one of our campaigners in the back

seat. Gordon, along with his PhD student Leigh Stearns, had already

plotted exactly where they wanted to place their precision GPS

receivers, a kilometer from the front of the glacier. But arriving at

the research coordinates, Gordon discovered something was missing.

"Yeah, it was quite a surprise when we came up here this morning," he

explained later, "and found that as we flew over the way points marked

for the survey grid, we were still over water and the calving front of

the glacier was quite a bit further up the fjord." He

was commuting to his place of work (a glacier of course) with Hughie,

flying the helicopter, and Melanie, one of our campaigners in the back

seat. Gordon, along with his PhD student Leigh Stearns, had already

plotted exactly where they wanted to place their precision GPS

receivers, a kilometer from the front of the glacier. But arriving at

the research coordinates, Gordon discovered something was missing.

"Yeah, it was quite a surprise when we came up here this morning," he

explained later, "and found that as we flew over the way points marked

for the survey grid, we were still over water and the calving front of

the glacier was quite a bit further up the fjord."

The Kangerdlugssuaq glacier has been surveyed using aerial and satellite

images since 1962. In all that time (and very likely for quite some time

before) its front has remained remarkably stable.

Now, over just a few years, it's retreated roughly three miles (5km).

Previous research, done by NASA, had shown the glacier thinning at a

rapid rate - about 33 feet (10m) per year. It had been a little puzzling

to Gordon how the glacier could thin so fast without retreating. As he

says, "Of course, when we flew over Monday morning, once we saw the

quite large retreat, it started to make sense."

A fast flowing ice river

Plotting a new research grid, Gordon and Leigh went about the work of

measuring how fast the ice that makes up this glacier is flowing

downhill.

Work

that was complicated by 20 knot winds, and a more chaotic glacial

surface than any they'd ever been on before [check]. Towering pinnacles

ready to collapse, tiny landing zones, and crevasses hidden under the

weathered surface by ice debris all hampered their efforts. Nonetheless,

the science team spent far longer out on this glacier than any other on

this trip - taking additional measurements to try and figure out what's

going on here. Work

that was complicated by 20 knot winds, and a more chaotic glacial

surface than any they'd ever been on before [check]. Towering pinnacles

ready to collapse, tiny landing zones, and crevasses hidden under the

weathered surface by ice debris all hampered their efforts. Nonetheless,

the science team spent far longer out on this glacier than any other on

this trip - taking additional measurements to try and figure out what's

going on here.

Their extra work paid off, though, and brought them another surprise.

When this glacier was last measured, in 1995, it was flowing at a fairly

speedy (for a glacier) 3.72 miles (6km) per year. Yet, preliminary

results from Gordon and Leigh's survey suggest that since then it's

speed has more than doubled, to almost nine miles (14km) per year -

making it one of the word's fastest. As Gordon put it, "that's pretty

staggering."

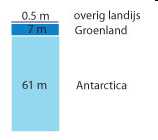

All this ice has to come from somewhere. In this case, as with many

other Greenland glaciers, it's flowing from the Greenland ice sheet. Not

that the ice sheet itself will disappear completely anytime soon. That

would take hundreds and hundreds of years.

But if the Kangerdlugssuaq glacier is an example of what's to come, then

it could go much faster than current models predict. In fact, we could

be looking at several feet of sea level rise over the next hundred years

- enough to wreck massive damage. More than 70 percent of the world's

population lives on coastal plains, and 11 of the world's 15 largest

cities are on the coast or estuaries. Weather patterns would also change

as the ice sheet shrinks. And the millions of gallons of melted ice

water would alter regional seawater salinity and global ocean currents.

In short, if the Greenland ice sheet is in fact draining rapidly it will

be a disaster of global proportions.

We'll keep doing our part by bringing you news from the frontlines of

climate change, but we need you to join us in action. Everyone needs to

pitch in, but if you're in the U.S. (the world's biggest global warming

polluter per capita) your help is especially needed.

|

Groenlandse gletsjer breekt alle records

Groenlandse gletsjer breekt alle records

He

was commuting to his place of work (a glacier of course) with Hughie,

flying the helicopter, and Melanie, one of our campaigners in the back

seat. Gordon, along with his PhD student Leigh Stearns, had already

plotted exactly where they wanted to place their precision GPS

receivers, a kilometer from the front of the glacier. But arriving at

the research coordinates, Gordon discovered something was missing.

"Yeah, it was quite a surprise when we came up here this morning," he

explained later, "and found that as we flew over the way points marked

for the survey grid, we were still over water and the calving front of

the glacier was quite a bit further up the fjord."

He

was commuting to his place of work (a glacier of course) with Hughie,

flying the helicopter, and Melanie, one of our campaigners in the back

seat. Gordon, along with his PhD student Leigh Stearns, had already

plotted exactly where they wanted to place their precision GPS

receivers, a kilometer from the front of the glacier. But arriving at

the research coordinates, Gordon discovered something was missing.

"Yeah, it was quite a surprise when we came up here this morning," he

explained later, "and found that as we flew over the way points marked

for the survey grid, we were still over water and the calving front of

the glacier was quite a bit further up the fjord."  Work

that was complicated by 20 knot winds, and a more chaotic glacial

surface than any they'd ever been on before [check]. Towering pinnacles

ready to collapse, tiny landing zones, and crevasses hidden under the

weathered surface by ice debris all hampered their efforts. Nonetheless,

the science team spent far longer out on this glacier than any other on

this trip - taking additional measurements to try and figure out what's

going on here.

Work

that was complicated by 20 knot winds, and a more chaotic glacial

surface than any they'd ever been on before [check]. Towering pinnacles

ready to collapse, tiny landing zones, and crevasses hidden under the

weathered surface by ice debris all hampered their efforts. Nonetheless,

the science team spent far longer out on this glacier than any other on

this trip - taking additional measurements to try and figure out what's

going on here.